Sed Jubilee

Hab Sed

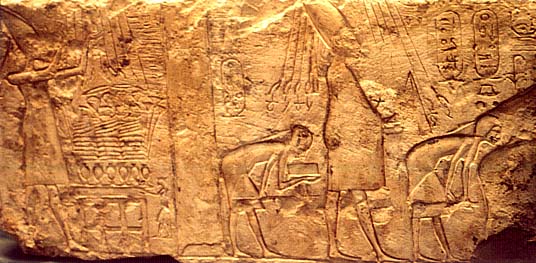

Akhenaton's Sed Festival, from Akhenaten and Tutankhamun: Revolution and Restoration

If an Egyptian pharaoh lived long enough to reach their thirtieth year of rule, they marked the occasion with a special jubilee called the Sed Festival, or Hab Sed. The origins of this festival probably dated back to the Predynastic Era, when ancient chieftains had to demonstrate their continued strength to rule or else be put to death in favor of a stronger, more battle-ready successor. The practice of ritual sacrifice was abandoned early in the Dynastic era, though, to be replaced instead by the much more people- (and pharaoh!) friendly Sed Festival.

The Hab Sed began on the first day of the first month, Tybi, of the season of Emergence, or Peret. On our calendar that would be mid-November. According to some accounts, the party would last for as much as two weeks. Unlike other feasts which centered around the gods, the Sed feast was a celebration of the king's vitality, which reflected upon the land's vitality. His rejuvenation ensured a continued bounty from the crops which would soon be emerging from the Nile floodplains, and his subjects probably shared in the festivities with music, feasting and dancing.

As part of the Sed observance, the pharaoh re-enacted his coronation and made offerings to the gods. He wore a distinctive cloak that covered his body down to his knees or further, as can still be seen on many monuments recording Sed observances. Another part of the ceremony called for the king to run around a special track, one part representing Upper Egypt, the other representing Lower Egypt. King Djoser, for whom the Step Pyramid was built, had a funeral complex built which included a special court that would allow him to continue celebrating the Hab Sed into eternity after his death.

The Sed rituals served to reaffirm the king's strength and worthiness to rule, as well as his endorsement by the gods. Some scholars have observed that statues commissioned of certain pharaohs after their first Sed jubilee seem more ethereal and god-like; it is possible that, after that milestone in their reign, they were looked upon as divine themselves. This idea may be supported by the meaning of the festival's name; Sed seems to mean "tail", which may refer to the bull's tail gods and pharaohs are often pictured wearing.

Following their first jubilee at Year 30, a ruling pharaoh would hold one every few years until their death. One notable exception would be during the reign of Akhenaton, who hosted a Sed jubilee during Year 2 or 3 of his rule. However, he was not celebrating a Sed for himself but actually for the god Aton, or perhaps for his deceased father Amunhotep III. Because Amunhotep III had presented himself as a living god, some scholars think that Akhenaton actually regarded his father as the earthly incarnation of Aton. He held royal Sed jubilees and used royal titles for Aton because he may have considered Aton and his father to be one and the same.

The Egyptians returned to traditional practices after Akhenaton's death, and had he lived to be forty or so, Tutankhamun would have celebrated his own Hab Sed in the customary manner. He ruled for only nine or ten years, but he was buried with ritual equipment to use in the afterlife for Sed Festivals into eternity. Party on!

References:

Brier, Bob. Ancient Egyptian Magic. New York: Quill Press, 1980.

Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane. Tutankhamen: Life and Death of a Pharaoh. New York: Penguin Books, 1984.

Silverman, David P., and Wegner, Josef W. and Jennifer Houser. Akhenaten and Tutankhamun: Revolution and Restoration. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2006.

Back to Temple Main Page